|

|

| Rae Lakes loop, Sixty Lakes Basin, Forester Pass in Kings Canyon National Park, California 6 day, 68 mile lasso loop through a watery Sierra wonderland |

Overview

| Rae Lakes Loop The Rae Lakes are a remote series of deep blue high alpine lakes in northern Kings Canyon National Park in the Sierra Nevada of central California. Their amorphous island-dotted shapes follow the contours of rocky mounds, peninsula's, marshes, meadows and ponds. Giant granite mountains with colorful names like Painted Lady, Dragon Peak and Fin Dome rise dramatically from their shores, mirrored in calm, crystal clear waters. The unique topography and lush, green terrain are a welcome respite from the rugged alpine surroundings, beckoning the adventurous backcountry enthusiast to stay and explore this watery wilderness playground. The only access is by trail and a two day hike from the nearest trailhead. The John Muir Trail (JMT) passes through the basin from north to south on it's way from Yosemite National Park to Mt. Whitney, the highest peak in the 48 contiguous states. The Rae Lakes Loop is a loosely named 46 mile circuit that climbs and descends two spectacular canyons to the high Rae Lakes basin. There is no "Rae Lakes Loop Trail" per se, the route simply assumes the loop shape of several existing paths. The trip begins at a place called Road's End, the eastern terminus of Hwy. 180 in the north of Kings Canyon National Park. You decide if you want to hike the lasso-shaped loop clockwise on the Woods Creek trail or counter-clockwise on the Bubbs Creek trail. Both directions entail a long climb up spectacular valleys beneath towering granite peaks along energetic streams, and both join the John Muir Trail for the north-south leg to the Rae Lakes basin. There is one high mountain pass to climb, 11,978 foot Glen Pass, at the southern end of the lakes basin. The trip can be done in four fast days, but planning an extra day or two would allow some additional time to enjoy the area and discover the surrounding terrain. The Rae Lakes Loop is reportedly one of the most popular multi-day hikes in the Sierra so you'll need to plan far in advance to score one of the coveted wilderness permits to hike here. |

Sixty Lakes Basin My hike included an extra day for exploring the adjacent Sixty Lakes Basin, which lies west over a high ridge from Rae Lakes. The only maintained trail to Sixty Lakes Basin begins on the west side of Rae Lakes. This is truly a pristine, virgin wilderness where rounding any bend in the terrain and topping every rise reveals another shimmering blue body of water, and often several more around it. Most of the lakes flow in to each other through a series of playfully cascading channels. Because many of the backpackers that come through this part of the Sierra are JMT through-hikers with schedules to keep, you will likely have these grass and flower-shored lakes all to yourself. There's only one path winding through the Sixty Lakes Basin, but the easy-to-traverse stone and grass terrain lends itself to freeform exploring. The Gardiner Basin, west above Sixty Lakes, is another adjacent alpine bowl full of lakes, with many square miles of rugged and remote terrain and numerous pristine lakes to discover, most above treeline and exposed. Some cross-country route-finding is required to explore Gardiner Basin properly, as there are few trails there and a challenging climb to access it. Gardiner Basin is what the Rae Lakes Loop "loops" around, as the high canyon walls of towering peaks separating it from the Rae Lakes loop trails are virtually impassable. Forester Pass This trip also included extra time for a 12 mile out-and-back spur trek south on the JMT to climb 13,200 ft. Forester Pass, one of the highest passes in the Sierra and the highest on the JMT. The climb south from the Rae Lakes Loop trail passes through some of the most dramatic terrain in the Sierra and the views from the heights around the pass are unforgettable. |

Trip Report

I'd been jones-ing to hike the Rae Lakes loop ever since I first saw some pictures of it. It is truly one of the most beautiful backcountry settings in the Sierra. I got the reservation for my Wilderness Permit online in May for my August trip and thoroughly planned out my route and the gear I'd bring. This is a pretty energetic hike with a lot of vertical gain/drop. Whether you choose to hike the loop clockwise or counter-clockwise, the first day and a half will be a steady climb up 1000's of feet in elevation, most of it a relatively gentle grade. It helped that I'd already been on several multi-day solo hikes in the previous months, been working out and jogging regularly, so I felt pretty good about my conditioning and gear. The lakes are at the highest part of the Rae Lakes Loop, so you'll be climbing up until you reach them. Only on Glen Pass does the trail climb higher than the Rae Lakes themselves. I took one hikers recommendation of doing the loop counter-clockwise, but in the end, I don't think it really matters - both directions pass through amazing mountainscapes and both start and end among dramatic settings. I planned on 4 days to and from Rae Lakes on this trip, and 2 additional days - one for exploring Sixty Lakes Basin west of Rae Lakes and the other for an out-and-back hike to either Gardiner Basin to the west or Forester Pass to the south, both alpine high country with remarkable scenery. This trip would be at a relaxed pace where I could take time to soak up all the scenery I wanted. After reading up and asking questions, I decided to forego the challenging cross-country route to remote Gardiner Basin on this trip and climb up Forester Pass instead.

I struggled to cut the number of photos to show of this hike down from the 1100+ I took to just 60 or so, but couldn't seem to get the final number below the 81 in the Pictures section and a few more in this trip report. Hope you enjoy.

Sunday Aug. 2, 2009

I threw my gear in the car and lit out of LA on a hot, clear morning for the long drive up through Bakersfield and Visalia to Hwy. 198/Generals Hwy. in Sequoia Kings Canyon National Park. I'd drive in and car camp near the trailhead tonight and strike out first thing. Paid my $20 entry fee at the Three Rivers park entrance, then drove north up the mountain through Giant Forest, threading through the thick woods until Hwy. 198 intersects with Hwy. 180 west to Fresno, where I turned east and continued deep into the wilderness to Roads End. 7 hours after I left LA, I pulled in to Moraine campground, the last of several on the road just before the eastern terminus of Hwy. 180 at Roads End.

Bear in campground

Sunday evening was a good choice to arrive as the weekend crowds had left and a lot of choice campsites were available. I gathered some wood, and cooked up dinner as the sun set, relaxing around a small but enjoyable campfire, then laid out my bag to sleep under the stars. The evening was winding down and people were having quiet conversations around dying campfires when the bear-in-the-campground hubris began from a few hundred yards through the trees. There was the usual banging of pots, whistling of whistles and people shouting. I trained my flashlight toward the area and watched a group of yelling guys with flashlights chasing a 350-400 pound brown bear through the trees. The harried bear would run ahead, then trot a little, probably thinking the guys would give up their chase any second, but they pursued hundreds of yards out of the campground and out to the highway before they turned back. I shone my light through the trees by the highway and watched him skulk off. I felt a little sorry for him, but was glad the guys took up the challenge of re-instilling concern of human contact into him. Most people just bang pots and yell until the bear moves away from their tent. He probably wandered through again after everyone was asleep.

| Day 1: Roads End to Vidette Meadows - 12.2 mi., +4230 ft. | ||

|

| Day 2: Vidette Meadows to Forester Pass - 10 mi., +3450 / -630 ft. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Trail / Conditions / Maps

| The Rae Lakes loop begins and ends at Road's End, the terminus of Hwy. 180 in northern Kings Canyon National Park. The loop route is 46 miles with almost 7000 ft. of elevation gain and 7000 ft. of drop. The average hiker can do it in 4 days, but 5 or more is recommended for side trips. In addition to Rae Lakes, this trip included out-and-back spur hikes to Forester Pass and to Sixty Lakes Basin, adding 22 additional miles—for a total of approximately 68 miles—and additional elevation gain of approximately 4600 ft and drop of same amount. |

The Sierra has long history of use by stock and you may have to share the trail with horses and mules at anytime. |

Directions / Permits / Links

| From north Los Angeles, it's approximately 314 miles to Road's End in Sequoia-Kings Canyon National Park's via the southwest entrance at Three Rivers, CA. It took me 7 hours up I-5, Hwy. 99 through Bakersfield and then Hwy. 198 east out of Visalia Wilderness permits are required for all overnight camping outside designated car campgrounds in Sequoia/Kings Canyon National Park. (SEKI). Day hikes do not require permits. If you've ever backpacked in a popular national park before, you know that you have to plan many, many months in advance as the quota for Wilderness Permits is filled early. Some permits are reserved for walk-in, first-come, first-served hikers. Reservations for a Wilderness Permit ($15) should be made online. Permits then need to be picked up in person the day before or before 9:00am the morning of the hike. Unlike other National Parks where you can pick up your permit at any Ranger Station, SEKI permits are issued based on the trailhead where you begin your trip and must be obtained from the permit station closest to your trailhead, which for this hike is the Road's End Permit Station. Permits must be carried by the trip leader at all times. |

In most of SEKI park, permit holders have free reign to camp pretty much where you want, as long as you follow the basics - e.g., 100 ft. from water, use existing sites when you can, etc. Campfires aren't allowed above treeline or in the Rae, Gardiner or 60 Lakes Basin. There are limits on where you can camp and for how many nights, even rules for using the steel bear boxes. (They're for JMT/PCT through-hikers only). During off-season, Sep. 26 - May 27—when the backcountry Ranger Stations are closed—there is no trailhead quota, no reservation required and Wilderness Permits are self-serve at the Visitor Centers and Permit Stations. |

|

| ||

Pictures

Getting there On the trail

Looking back west at the valley just climbed up, about 3 miles from Roads End trailhead |

Big peaks scrape the sky on both sides of the canyon up |

Bubbs Creek becomes a noisy waterfall near Junction Meadow |

Panorama south (L) and west (R) from above the falls |

||

Formidable walls of jagged granite line the north canyon. On the other side is Gardiner Basin, a remote lost land of alpine lakes. |

Bubbs Creek carves a deep gorge near Junction Meadow |

Bubbs Creek trail follows rushing water beneath towering peaks |

Morning of day 2, a spur trip south on the JMT to climb Forester Pass. Looking north down the valley just ascended from the Rae Lks. loop trail. |

||

The Sierra gives up the perfect colors one expects from a mountain paradise. |

At the edge of treeline is a final lush meadow basin before tackling the long ascent to Forester Pass. The trail climbs the valley between the two mountains. |

A pair of hikers cool off at the meadow's lake, hidden from the trail behind a stony bluff |

A backpacker silhouetted against a swarm of fast-moving clouds |

Looking north at the lunarscape valley just climbed |

View southeast at peaks that share the ridge with Forester Pass, out of view on the right |

The colors and shapes tell a tale of violent beginnings |

Large tarn near the final miles to the pass |

Fast-moving clouds played in the sun, splashing shadowy colors onto the Range of Light. View north of Kings Canyon National Park near Forester Pass from the John Muir Trail. |

Even in late summer, there's a bank of snow and ice to cross, in places waist deep if you posthole in the wrong spot. |

The other/south side of Forester Pass. Stone embankments support the steep switchbacked trail below the pass (top right). |

|

The dramatic high alpine view south (L) and west (R) from atop Forester Pass. You can make out the trail in the bottom center |

Looking back at Forester Pass, a notch in the very center of the photo, from a mile south |

Early morning of day 3, view north from the top of Forester Pass Early morning of day 3, view north from the top of Forester Pass |

The color of the water is unreal |

Many JMT through-hikers camp below the passes and climb them first thing |

|

A morning view of the meadow basin north of Forester Pass. A trail crew is climbing up to go to work (bottom center) |

The meadow lake again in the warm morning sun. |

Unusual stone-filled hole, shaped like an arrow. |

The grass in the meadow is soft and spongy and the banks of the stream seemed almost landscaped The grass in the meadow is soft and spongy and the banks of the stream seemed almost landscaped |

Valley north between Forester and Glen Passes |

Bubbs Creek |

Giant dead trees add color |

Awesome pyramidal E. Vidette Peak towers above the canyon south to Forester Pass |

Charlotte Lake, view west |

Large primal meadow west of Charlotte Lake. Rivulets and miniature streams wind through the spongy sod |

||

Charlotte Lake from the JMT. View southwest to the distant peaks of the Great Western Divide Charlotte Lake from the JMT. View southwest to the distant peaks of the Great Western Divide |

Charlotte Dome in a spur valley west of the JMT between Charlotte Lk. and Glen Pass |

Looking south at the final basin from which the ascent to Glen Pass begins in earnest. |

Above a bowl of impassibly high walls, Glen Pass is a small notch in the center of the ridge Above a bowl of impassibly high walls, Glen Pass is a small notch in the center of the ridge |

View south from the top of Glen Pass. You can see the trail winding above the tarn |

|

First glimpse north at the Rae Lakes basin from atop Glen Pass. The John Muir Trail wraps around the tree-lined lakes at the upper right and continues north |

Hikers make their way down from Glen Pass. Well, you'll just have to take my word for it - it's a big hill. |

Dusk brings a satiny deep blue sheen to the big south Rae Lake |

|||

Morning of day 4. Fin Dome towers over the deep blue Rae Lakes in this view south |

The Rae Lakes have numerous islands and channels, isthmus' and peninsulas. The Rae Lakes have numerous islands and channels, isthmus' and peninsulas. |

HIkers make their way up to the pass for Sixty Lakes Basin. HIkers make their way up to the pass for Sixty Lakes Basin. |

Rae Lakes in the Sierra Nevada of Kings Canyon National Park, California. Center left is Dragon Peak, far right is Painted Lady. View north (L) to south (R) from the trail to Sixty Lakes Basin. |

Rae Lakes from atop the pass to Sixty Lakes. |

|

The Sixty Lakes Basin, looking northwest |

Sixty Lks. is a pristine wilderness you'll have all to yourself |

Lake after lake appear at every turn, over every rise |

|

Creeks channel the water from one lake to another |

|

Dead trees can stay standing for decades |

Giant peaks peer into the basin on all sides |

The back (west) side of Fin Dome in this view south |

Sixty Lakes Basin in Kings Canyon National Park, CA. 180 degree panorama from north (left) to south (right) |

||

An endless variety of one amazing lake after another |

After a full day of exploring, it was time to head back |

A last look back north |

|||

The first of the 60 Lks. near the top of the access pass |

Descending back to Rae Lks. in the late afternoon sun. |

Morning of day 5 and leaving Rae Lakes basin. View south (L) and west (R) from the John Muir Trail |

One of the final Rae Lakes seen as the JMT descends north. |

Handsome red trees flourishing in a rugged setting. From the other side, the northern exposure, they are an indistinct shade of brown. |

|

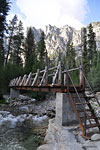

Approaching the swinging bridge above Woods Creek where the JMT meets the Woods Creek trail |

They aren't kidding about one at a time - it really sways! |

West of the swinging bridge and after leaving the JMT, the Woods Creek trail descends through Castle Domes valley, one of my favorite of the trip |

Photos can't capture the soaring heights of the the surrounding peaks |

||

A dramatic trio on the ridgeline |

View south from the Woods Creek trail in the Castle Domes valley |

Every few minutes another unique mountain formation comes into view |

After days of granite and thick forest, the wide, grassy Castle Domes Meadow is a welcome change |

||

View east back to Castle Domes valley along the Woods Creek portion of the Rae Lakes loop, between Paradise and the JMT. |

A giant Sugar Pine tree reaching for the clouds |

I had lunch, relaxed, read my book and lingered here for an hour |

|||

Looking west toward Paradise Valley, a steep canyon connecting Roads End in the west with the John Muir Trail to the east |

Paradise Valley looking west |

Day 6 and Mist Falls from above |

Mist Falls is a destination for dayhikers from Roads End |

||

The final few miles west below Mist Falls |

Granite ridge above the flat sandy trail near the Road's End trailhead offers a taste of things to come |

More photos in the Trip Report top of page |

|||

TOP

Since 11.09